Some thoughts of Gawain about the decline in church attendance being the result of a lack of art in the church struck a familiar chord. I was a choir director for a number of years at a Lutheran Church. The Lutherans are a funny lot, liturgically speaking. They have all the liturgical traditions of their closest denominational relatives (Anglicans and Catholics), and yet one would be hard pressed to find this rich liturgical inheritance practiced with any regularity here in Canada.

There is no equivalent movement in Lutheranism to rival Anglo-Catholicism, so the only option for those Lutherans who are more liturgically inclined is to either move to Waterloo, Ontario, where the Lutheran community is large and diverse, and you have great men like Pastor Paul Bosch concerned about liturgy, or, failing that, attempt to bring the liturgical practices that have been there all along, right in pages of the Lutheran Book of Worship they crack open every Sunday, into their own church.

This, my friends, is also known as "pissing into the wind".

For five years, the church pastor and I attempted to bring art and liturgy pack into cold, empty space that was the church. The members of the congregation who were most opposed to these changes also happened to be the most vocal. Support for the reintroduction of weekly communion or the presence of an altar cross would be whispered to us, as though people feared for their lives if their views got out.

The strangest part about the entire exercise was that the main objection to the changes, most of which were very minor, was that we were changing their traditional ways of worship. But here's the thing, and I wonder if others who have been in protestant churches in the past 25 years have noticed the same thing - there are no traditional ways of worship in most churches outside the liturgical orbit of Catholicism. If you asked one group what the liturgical tradition for say, Christmas was, you'd get one answer. You asked another group, you'd get a completely different answer. Many of the immovable "traditions" were things they had only started doing a few years before. Which led us to believe we were working with a blank slate. What a blunder.

So why did they object so much to what amounted to, in effect, a kind of liturgical Counter-Reformation? A return to their own lost traditions.

The only answer we could ever come up with was that they didn't like what they took to be the "Catholicisation" of their church. Most of these people had grown up still firmly under the impression that the Catholics were all going to hell and that a service that resembled theirs would perhaps imply to God that we too were a popish lot, and God might send us to hell too. For celebrating the Eucharist every week. Never mind that in 1997, Lutherans and Catholics signed a document that from a theological perspective, ended the Reformation.

***

How does one explain this kind of thing? I recognize now that, as someone who wasn’t a Lutheran, just how important these things were to them. What was so important to these people, that were they willing to tear the church apart to keep it out? It was art.

Contrast this with all these wonderful posts over at Heaven Tree about Bali, their culture, and how their life is infused with a kind of aesthetic sensibility, where cab drivers become kings and bureaucrats become gods. Here was a group, upper-middle class and quite worldly, for whom the thought of a more dramatic service or a more colourful church was anathema. These people completely lacked the aesthetic sense so palpable in other parts of the world. For them all that mattered was the Word, and even then, a sermon with too much metaphor and cadence was tut-tutted at coffee hour.

The pastor and I worked to change the services precisely because we believed that if anything was going to “save” the church, it wasn’t going to be jacking up the fees for using the parking lot, or changing more for weddings and funerals (this was the church consensus – revenue generation as solution to spiritual ills). Instead, it was going to be by restoring the active participation of the congregation in the church services they attended. The only way to do this was through a return to the magic and mystery of the ancient rites, because they were the only thing that could attract people who didn’t care for God back into the church.

In other words, we wanted to turn the church into the Bali Arts Festival. And how bad would that have been?

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Why oh Why

did I do it?

Why did I find myself this morning checking out the National Post?

I haven't been over there since they put up the paywall. I used to enjoy reading Mark Kingwell, and let's be honest, when that paper was born, neo-con zaniness aside, the arts and culture section couldn't be beat by any newspaper in the country.

But....that was so long ago. The paper seems a pale, yet strangely angry, shadow of itself. Funny too, that anger, given they've got Steve Harper in Ottawa now. Corcoran's still peddling his missives that would make the editorial board of the Wall Street Journal blush, but, true to my own form, and this blog, the article I found myself reading was the following screed by William Watson, who happens to be an economics professor at McGill.

The title let me know I was going to be in for a 1990's right-wing anger fest - "Let social activists pay for the CBC". Aaaaah....the old "activists" trope. Boy, I haven't heard that one in years. I thought it kind of died out, what with Steve Harper, of National Citizens Coalition fame, being PM.

One would think a Yale-trained economist who writes for the Post would have received the memo that "activist" is a word that should be used sparingly, what with all those corporatist bagmen, like the PM and his Secretary, Jason Kenny, formerly of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation, running the country. (Don't you love those quaint populist names for these tax the poor, free the rich social activist groups?)

But I digress. So, let's get back to what this Yale-trained economist has to say about CBC radio. He poses a nice, clear question: "Why should we be subsidizing what so often amounts to social activist radio?"

Well, let's see - I take it Professor Watson here is going to now answer this question by providing evidence of CBC radio's "social activism" (what a wink wink nudge nudge term "social activism" is - it's akin to a conservative secret handshake, like "special interest" and "the poor" - the latter always said with just a dusting of approbation).

So what does the dear professor take social activism to be? Everything he heard on the CBC that day. It's just that simple. Really.

I won't bore you with rehashing the litany of things he found distasteful about the CBC that day, because it's just one of those things about the right-left divide in politics. I look at the list and go, hey, what a bunch of interesting things to learn about - and he goes, why aren't we discussing what a dream globalization is? Or why aren't there more Hayek and Friedman discussions on the CBC? In other words, why is Professor Watson's kind of social activism not being discussed?

And in it's own way, it's a good question. The CBC should have "free-market supporters" (read here corporatist windbags, these guys wouldn't know a free market if they wound up standing in the middle of one looking for a pair of socks - they all have an all too narrow view of equality) like William Watson on, and let him go head to head with Judy Rebick or someone like that.

I mean, it's not as though Watson and his kind don't have a pulpit (The National Post, and to a lesser extent, the Globe and Mail), but sure, let them, even more often than they already are, on the CBC - because then all the social activists are there, like Professor Watson, free market activist, and no one can use that old, tired phrase, because the social activists are paying for the CBC

Then we can actually get on to a discussion about what's really wrong with the CBC, which isn't much of CBC radio One (Professor Watson doesn't appear to know there are two CBC Radio stations). Oddly enough, the problems stem from the fact that the CBC has adopted a lot of the 1990's neo-con corporatist psychobabble and has essentially refashioned itself into precisely what these guys wanted institutionally, except that in doing so it has lost much of what made it utterly different from private broadcasting.

That Professor Watson couldn't even identify the real problem on CBC Radio, Radio Two, just goes to show how out of touch he is with things here in the public world - perhaps he should climb down from his ivory tower and spend a bit more time checking things out before proclaiming that social activists like him should be paying for the CBC.

And here's the irony - I suspect that Professor Watson and I would agree on something - that the death of an elitist streak at the CBC over the past 15 years has been perhaps the greatest blow to its strengths, and has helped to make foes from friends and deliver it to the very enemies of anything public, like William Watson.

I mean this - I would love nothing more than to find some hard-core institutional economist wipe the floor with Professor Watson's rehashed, tired, one-sided musings about the glories of the free market and competition. (I understand this is hard, seeing as most good economists spend their time doing research instead of penning anti-CBC smears that look like they were written in 1992).

I'd love to see intellectual rigour brought back to every nook and cranny of the CBC - because it's exactly what this country needs to stem the damaging of discourse by smart men peddling shallow ideas.

Why did I find myself this morning checking out the National Post?

I haven't been over there since they put up the paywall. I used to enjoy reading Mark Kingwell, and let's be honest, when that paper was born, neo-con zaniness aside, the arts and culture section couldn't be beat by any newspaper in the country.

But....that was so long ago. The paper seems a pale, yet strangely angry, shadow of itself. Funny too, that anger, given they've got Steve Harper in Ottawa now. Corcoran's still peddling his missives that would make the editorial board of the Wall Street Journal blush, but, true to my own form, and this blog, the article I found myself reading was the following screed by William Watson, who happens to be an economics professor at McGill.

The title let me know I was going to be in for a 1990's right-wing anger fest - "Let social activists pay for the CBC". Aaaaah....the old "activists" trope. Boy, I haven't heard that one in years. I thought it kind of died out, what with Steve Harper, of National Citizens Coalition fame, being PM.

One would think a Yale-trained economist who writes for the Post would have received the memo that "activist" is a word that should be used sparingly, what with all those corporatist bagmen, like the PM and his Secretary, Jason Kenny, formerly of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation, running the country. (Don't you love those quaint populist names for these tax the poor, free the rich social activist groups?)

But I digress. So, let's get back to what this Yale-trained economist has to say about CBC radio. He poses a nice, clear question: "Why should we be subsidizing what so often amounts to social activist radio?"

Well, let's see - I take it Professor Watson here is going to now answer this question by providing evidence of CBC radio's "social activism" (what a wink wink nudge nudge term "social activism" is - it's akin to a conservative secret handshake, like "special interest" and "the poor" - the latter always said with just a dusting of approbation).

So what does the dear professor take social activism to be? Everything he heard on the CBC that day. It's just that simple. Really.

I won't bore you with rehashing the litany of things he found distasteful about the CBC that day, because it's just one of those things about the right-left divide in politics. I look at the list and go, hey, what a bunch of interesting things to learn about - and he goes, why aren't we discussing what a dream globalization is? Or why aren't there more Hayek and Friedman discussions on the CBC? In other words, why is Professor Watson's kind of social activism not being discussed?

And in it's own way, it's a good question. The CBC should have "free-market supporters" (read here corporatist windbags, these guys wouldn't know a free market if they wound up standing in the middle of one looking for a pair of socks - they all have an all too narrow view of equality) like William Watson on, and let him go head to head with Judy Rebick or someone like that.

I mean, it's not as though Watson and his kind don't have a pulpit (The National Post, and to a lesser extent, the Globe and Mail), but sure, let them, even more often than they already are, on the CBC - because then all the social activists are there, like Professor Watson, free market activist, and no one can use that old, tired phrase, because the social activists are paying for the CBC

Then we can actually get on to a discussion about what's really wrong with the CBC, which isn't much of CBC radio One (Professor Watson doesn't appear to know there are two CBC Radio stations). Oddly enough, the problems stem from the fact that the CBC has adopted a lot of the 1990's neo-con corporatist psychobabble and has essentially refashioned itself into precisely what these guys wanted institutionally, except that in doing so it has lost much of what made it utterly different from private broadcasting.

That Professor Watson couldn't even identify the real problem on CBC Radio, Radio Two, just goes to show how out of touch he is with things here in the public world - perhaps he should climb down from his ivory tower and spend a bit more time checking things out before proclaiming that social activists like him should be paying for the CBC.

And here's the irony - I suspect that Professor Watson and I would agree on something - that the death of an elitist streak at the CBC over the past 15 years has been perhaps the greatest blow to its strengths, and has helped to make foes from friends and deliver it to the very enemies of anything public, like William Watson.

I mean this - I would love nothing more than to find some hard-core institutional economist wipe the floor with Professor Watson's rehashed, tired, one-sided musings about the glories of the free market and competition. (I understand this is hard, seeing as most good economists spend their time doing research instead of penning anti-CBC smears that look like they were written in 1992).

I'd love to see intellectual rigour brought back to every nook and cranny of the CBC - because it's exactly what this country needs to stem the damaging of discourse by smart men peddling shallow ideas.

Tuesday, July 18, 2006

The Naxos Music Library

So I was returning some books to the Music Library at the University of Toronto, and I espied a sign that said "the Naxos Music Libary is now available to students".

My thoughts turned - does that mean what I think it does? After coffee with my chums, I settled down to my work computer, and after finding the proper link (they make it nice and difficult to find), I found myself logged into this.

Good freaking Lord! Holy Mary Mother, Mother of the Sweet, Sweet Baby Jesus!

Since discovering this er, yesterday afternoon, I've listened to Iranian Classical Music, the Ramayana monkey chant, operatic overtures by Franz Schreker, the First book of Madrigals by Claudio Monteverdi, as well as his Ballo Delle Ingrate and Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda. Right now, I'm listening to the Preludes of Charles Valentin Alkan.

This is serious. It will change my relationship with my family and friends - there will never be a lack of new, obscure music playing in my head or my house.

Now I know there are some of you out there, lurking, saying, "Naxos is the Wal-Mart of classical music! Your love of this is condoning the very things you despise in other spheres of cultural life!"

The availability of this kind of knowledge, where I can sit my toddler son down and teach him more about classical music aurally than I could have dreamed of doing myself in all my years as a student is exactly the kind of thing I wish there was more of in our capitalist society - this is precisely the place where, if capitalism works, more power to it. If dumping the riches of western civilization onto the Internet is profitable to Naxos, hey, who am I to complain? If classical musicians, some of whom I know, make some money by recording for Naxos, hey, all the better - it's not like they're whipping Indonesians children into finishing up that last batch of porcelain nativity scenes.

This is really all a meandering way of saying that if you have institutional access to this service, use it, and if you don't, the monthly cost is fairly reasonable for what you get in return.

And to completely scare the last of you off, this also means there's going to be a lot more music talk on this site!!

My thoughts turned - does that mean what I think it does? After coffee with my chums, I settled down to my work computer, and after finding the proper link (they make it nice and difficult to find), I found myself logged into this.

Good freaking Lord! Holy Mary Mother, Mother of the Sweet, Sweet Baby Jesus!

Since discovering this er, yesterday afternoon, I've listened to Iranian Classical Music, the Ramayana monkey chant, operatic overtures by Franz Schreker, the First book of Madrigals by Claudio Monteverdi, as well as his Ballo Delle Ingrate and Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda. Right now, I'm listening to the Preludes of Charles Valentin Alkan.

This is serious. It will change my relationship with my family and friends - there will never be a lack of new, obscure music playing in my head or my house.

Now I know there are some of you out there, lurking, saying, "Naxos is the Wal-Mart of classical music! Your love of this is condoning the very things you despise in other spheres of cultural life!"

The availability of this kind of knowledge, where I can sit my toddler son down and teach him more about classical music aurally than I could have dreamed of doing myself in all my years as a student is exactly the kind of thing I wish there was more of in our capitalist society - this is precisely the place where, if capitalism works, more power to it. If dumping the riches of western civilization onto the Internet is profitable to Naxos, hey, who am I to complain? If classical musicians, some of whom I know, make some money by recording for Naxos, hey, all the better - it's not like they're whipping Indonesians children into finishing up that last batch of porcelain nativity scenes.

This is really all a meandering way of saying that if you have institutional access to this service, use it, and if you don't, the monthly cost is fairly reasonable for what you get in return.

And to completely scare the last of you off, this also means there's going to be a lot more music talk on this site!!

Monday, July 17, 2006

Why the Financial Times is my Weekend Paper; or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Liberalism

Does everyone, at some point, realise they've come to a certain place in their life where it's both a social and personal necessity to have the newspaper delivered to their door?

It happened so innocently. This young boy, clever and confident, came to my door last summer with an offer I couldn't refuse - a 7-day subscription to the Toronto Star at a price lower than the cost of weekend paper at the news stand!

This boy, who I'm sure will one day sell air conditioners in Iqualuit (if only that were a description of his future prowess as a merchant), dashed off to an idling mini-van where, I presume, his parents or local paper kingpin (or both) produced the required paperwork to put him one sale closer to a free Schwinn bike (with tassels) or bubble hookah.

And I waited eagerly for that first paper. Then, one morning, a dull thud at the porch. The paperboy! Or, more accurately, the paperguy in his mid-40's with the paisley bellhop's hat. I rushed downstairs, opened the door, and there it lay - my first paper. It wasn't in swaddling or a basket, but for the next few minutes, this paper was my baby.

Unfortunately, unlike the real baby I was home looking after, the daily Toronto Star soon became a pile of unread scrolls left to dessicate at the bottom of our entranceway. Some days we wouldn't even bring the thing inside until the following day. Some baby- some parent.

Then there was the weekend paper. Am I the only one who has trouble reading the Saturday Toronto Star? This enormous beast, a giant prop for the local car manufacturing and real estate industries, and the sheer number of pages devoted to selling you things, or telling you where to buy things, or what kinds of new things there are out there to buy, or where you can go eating while you shop for those new things, or...

Like the previous paragraph, the Saturday newspaper quickly became a burden best abandoned. The only bright spot in all of this was the Sunday Star - Not only could you finish the paper, but there were actually moments when the Star managed to climb out of its intellectually wishy-washy over-earnestness and produce something genuinely interesting.

So I decided, after four short months, to abandon all but the Sunday edition, which is compact, with lots of articles and is overall a decent attempt to raise the intellectual and cultural bar of the paper.

Alas, I needed to fill the newspaper vacuum. I starting buying the Saturday Globe and Mail, but, like any rebound, I enjoyed immensely it for a while but soon found myself bored and looking for something a bit more sophisticated, more exotic. And I found it in the Financial Times.

“Wuzzah?” I hear you saying in your head, “I thought you were some kind of post-structuralist Marxist – what’s a guy who knits his own hemp socks doing buying the Financial Times?”

Well, dear readers, I’ll tell you – it’s a great paper! Despite the title, it bears little resemblance to that corporatist Pravda, the Wall Street Journal. It does have stock prices, but it also has well-written editorials which present a well-thought out, decidedly liberal view of the world. All this on that distinctive salmon-coloured newsprint. Most importantly, and this is who brought me to the paper in the first place, it has Tyler Brûlé.

But that’s for another time.

It happened so innocently. This young boy, clever and confident, came to my door last summer with an offer I couldn't refuse - a 7-day subscription to the Toronto Star at a price lower than the cost of weekend paper at the news stand!

This boy, who I'm sure will one day sell air conditioners in Iqualuit (if only that were a description of his future prowess as a merchant), dashed off to an idling mini-van where, I presume, his parents or local paper kingpin (or both) produced the required paperwork to put him one sale closer to a free Schwinn bike (with tassels) or bubble hookah.

And I waited eagerly for that first paper. Then, one morning, a dull thud at the porch. The paperboy! Or, more accurately, the paperguy in his mid-40's with the paisley bellhop's hat. I rushed downstairs, opened the door, and there it lay - my first paper. It wasn't in swaddling or a basket, but for the next few minutes, this paper was my baby.

Unfortunately, unlike the real baby I was home looking after, the daily Toronto Star soon became a pile of unread scrolls left to dessicate at the bottom of our entranceway. Some days we wouldn't even bring the thing inside until the following day. Some baby- some parent.

Then there was the weekend paper. Am I the only one who has trouble reading the Saturday Toronto Star? This enormous beast, a giant prop for the local car manufacturing and real estate industries, and the sheer number of pages devoted to selling you things, or telling you where to buy things, or what kinds of new things there are out there to buy, or where you can go eating while you shop for those new things, or...

Like the previous paragraph, the Saturday newspaper quickly became a burden best abandoned. The only bright spot in all of this was the Sunday Star - Not only could you finish the paper, but there were actually moments when the Star managed to climb out of its intellectually wishy-washy over-earnestness and produce something genuinely interesting.

So I decided, after four short months, to abandon all but the Sunday edition, which is compact, with lots of articles and is overall a decent attempt to raise the intellectual and cultural bar of the paper.

Alas, I needed to fill the newspaper vacuum. I starting buying the Saturday Globe and Mail, but, like any rebound, I enjoyed immensely it for a while but soon found myself bored and looking for something a bit more sophisticated, more exotic. And I found it in the Financial Times.

“Wuzzah?” I hear you saying in your head, “I thought you were some kind of post-structuralist Marxist – what’s a guy who knits his own hemp socks doing buying the Financial Times?”

Well, dear readers, I’ll tell you – it’s a great paper! Despite the title, it bears little resemblance to that corporatist Pravda, the Wall Street Journal. It does have stock prices, but it also has well-written editorials which present a well-thought out, decidedly liberal view of the world. All this on that distinctive salmon-coloured newsprint. Most importantly, and this is who brought me to the paper in the first place, it has Tyler Brûlé.

But that’s for another time.

Wednesday, June 14, 2006

Joining the Conversation

I'm immensely enjoying the debate between Theo and Gawain and Conrad over at Heaven Tree and the Varieties of Unreligious Experience, although I cannot help but think that they’re not really arguing, in the sense that one is asserting X and the other not-X. Instead, I’m seeing this as the putting in to play of two (of many) competing kinds of philosophical method.

To lay my cards on the table, I have a great sympathy for Conrad’s defence of Plato. Although I’ve never read him in Greek (does that make me illiterate?) I enjoy Plato for the same reasons I suspect many people do – he’s a great writer.

Does he have the occasional straw man? Ion comes to mind, but as Conrad notes, if you can make your way through Parmenides (I found it harder than Wilfrid Sellars), it’s remarkable to watch Plato turn his dialectical guns on his own vaunted Theory of Forms, laying the groundwork for Aristotle’s later criticisms. Plato was a formidable, unrelenting thinker.

My own thoughts about Plato is that had he had the logical tools available to him, perhaps he would have realised that the reason he could not pin down terms like “truth” or “beauty” via definition was because the ways in which these terms can be used exceeds our ability to define them. That is, the fact that the meaning of beauty is to some extent undecideable isn’t a strike against beauty as a useful or important word, but a reflection of the place the word occupies in the logical and conceptual space of human life.

I’m trying to walk a fine line here – I’d like to affirm that Gawain’s (phenomenologically-inclined?) naturalised view of aesthetics has promise, but that this has little bearing on the fact that there are also very likely many unnatural ways for things to be beautiful, and that these unnatural ways can be shaped and guided by the forms of discourse we participate in. There’s a normative element here that I’m not sure Gawain’s approach can, or will ever capture. And my friend, this isn’t a strike against you in my eye, just part of the fun.

So this is where my sympathies with Conrad’s claim about the importance of Plato in talking about beauty lie – Plato set us down a methodological path that, like it or not, has shaped the way in which debates about beauty are conducted, scientific ones included, in much the same way Descartes, in his Meditiations, set the agenda for epistemological debates for hundreds of years. And within these debates, we may find new kinds of beauty, kinds that will never find their way into the realm of experimental psychology.

Moreover, definitions are important, aren’t they? Knowing what beauty is, or perhaps more importantly, what beauty is not, will have a great influence in how one would go about coming up with experiments to determine how people deal with beauty.

Much, no all, of philosophy is wrestling with texts, taking on their histories and their concepts, living them and responding to them in a meaningful kind of way. To my mind, the best part about philosophy is that Plato is still relevant, that we can enjoy him on an intellectual level, watching Socrates in the agora corrupting the young men of Athens, and finding ourselves ensnared by the same thoughts they were.

Although I don’t share Richard Rorty’s relativism, I’m not so bothered by his talk about philosophy as a kind of conversation, an engagement, to which I’d like to add, in the words of A.P. Martinich, can give birth to a science. This is one of the wonders of philosophy, that in the constant churning and working out of thoughts, one can rise from their armchair and make their way out to the world, to the lab, to life.

This has been a fascinating discussion that has forced me to think in new ways. I don't know about all of you, but that's all I really need right now!

To lay my cards on the table, I have a great sympathy for Conrad’s defence of Plato. Although I’ve never read him in Greek (does that make me illiterate?) I enjoy Plato for the same reasons I suspect many people do – he’s a great writer.

Does he have the occasional straw man? Ion comes to mind, but as Conrad notes, if you can make your way through Parmenides (I found it harder than Wilfrid Sellars), it’s remarkable to watch Plato turn his dialectical guns on his own vaunted Theory of Forms, laying the groundwork for Aristotle’s later criticisms. Plato was a formidable, unrelenting thinker.

My own thoughts about Plato is that had he had the logical tools available to him, perhaps he would have realised that the reason he could not pin down terms like “truth” or “beauty” via definition was because the ways in which these terms can be used exceeds our ability to define them. That is, the fact that the meaning of beauty is to some extent undecideable isn’t a strike against beauty as a useful or important word, but a reflection of the place the word occupies in the logical and conceptual space of human life.

I’m trying to walk a fine line here – I’d like to affirm that Gawain’s (phenomenologically-inclined?) naturalised view of aesthetics has promise, but that this has little bearing on the fact that there are also very likely many unnatural ways for things to be beautiful, and that these unnatural ways can be shaped and guided by the forms of discourse we participate in. There’s a normative element here that I’m not sure Gawain’s approach can, or will ever capture. And my friend, this isn’t a strike against you in my eye, just part of the fun.

So this is where my sympathies with Conrad’s claim about the importance of Plato in talking about beauty lie – Plato set us down a methodological path that, like it or not, has shaped the way in which debates about beauty are conducted, scientific ones included, in much the same way Descartes, in his Meditiations, set the agenda for epistemological debates for hundreds of years. And within these debates, we may find new kinds of beauty, kinds that will never find their way into the realm of experimental psychology.

Moreover, definitions are important, aren’t they? Knowing what beauty is, or perhaps more importantly, what beauty is not, will have a great influence in how one would go about coming up with experiments to determine how people deal with beauty.

Much, no all, of philosophy is wrestling with texts, taking on their histories and their concepts, living them and responding to them in a meaningful kind of way. To my mind, the best part about philosophy is that Plato is still relevant, that we can enjoy him on an intellectual level, watching Socrates in the agora corrupting the young men of Athens, and finding ourselves ensnared by the same thoughts they were.

Although I don’t share Richard Rorty’s relativism, I’m not so bothered by his talk about philosophy as a kind of conversation, an engagement, to which I’d like to add, in the words of A.P. Martinich, can give birth to a science. This is one of the wonders of philosophy, that in the constant churning and working out of thoughts, one can rise from their armchair and make their way out to the world, to the lab, to life.

This has been a fascinating discussion that has forced me to think in new ways. I don't know about all of you, but that's all I really need right now!

Monday, May 22, 2006

Street Archeology: Ossington Avenue, Toronto

This is a departure from the usual fare of well, not much lately, but I hope you'll enjoy this stroll along one of Toronto's most interesting and evocative north/south streets – Ossington Avenue. I suppose you could call this a flâneur, as I do like to fancy myself an acute observer of street and social life. However, there was no one around Ossington today, due to it being a holiday (Victoria Day) here in Canada.

Moreover, instead of stealing from Beaudelaire and Benjamin, I'd prefer steal a concept from Foucault – well, I'm not even really stealing it from him either, I'm really just name dropping - and take you on a kind of archaeological dig through the history of Ossington as I imagine it to be. Our tools will be unequal parts empirical and conjectural, and best of all, there will be photos.

When you come at Ossington, heading south from Dundas Street, you find yourself in the centre of the Rua Açores, one of the Portuguese areas of the city.

[An aside. Toronto self-identifies itself as a massive agglomeration of “villages”, represented by street signs letting you know what “village” you're in. Could it be that nice-looking street signs are a major reason why Toronto is, for the most part, a decent place to live? I wonder how all the people who live in these areas deal with the kind of village they're a part of. And if you think they don't, consider this – I'm rooting for Portugal in the World Cup this year.]

Here you have some of the elements of what makes an area “ethnic” - the local butcher and fishmonger sell dead things with their heads on them. The peixaria pictured above is a particularly interesting and affordable place to buy fish from. You won't find sushi-grade tuna there, but there are a kinds of fish there that I've never seen anywhere else in the city.

The papelaria in the photo is also a sign of another ethnic influence on Ossington – Vietnamese. Yes, the Papelaria Portugal is run by a Vietnamese family. And so here we find the two communities who make up what I'll call the “ethnic presence” on Ossington – Vietnamese and Portuguese. (yes, that is a strip club above the pool hall).

The Portuguese presence appears to manifest itself through food and building materials. The Portuguese community is well known in Toronto for helping to supply manual and skilled labour in the building trades for the booming construction industry here, although a good number of Portuguese were recently deported back to Portugal by the Conservative government.

So there are hardware stores, kitchen and bath stores, bakeries and fishmongers – one could do nearly all their renovating shopping on a single block of Ossington.

The Vietnamese presence is very different. Where the Portuguese community lacks restaurants, the Vietnamese community abounds. I believe there are six Vietnamese restaurants on Ossington Avenue between Queen Street and Dundas Street. Many of these restaurants also have Karaoke, as you can see from the picture below.

Ossington wasn't always this way. If the information on this site is correct, Ossington's name, like many streets in Toronto, is an homage to a distant British nobleman. In this case, the 1st Viscount Ossington, John Evelyn Denison, whose family owned the area immediately west of Ossington.

Ossington is also home to those seeking refuge from the crowds and rents of Queen Street West. Also known as West Queen West, the area along Queen to the east and west of the foot of Ossington is arguably the hippest place in the city, with shops, art galleries and restaurants galore. One can see how West Queen West is beginning to bleed over onto Ossington, just as the Portuguese influence made its way south along Ossington from Dundas. In between these two influences is a kind of everyman's land, where old and new mix with the hip and ancient.

Take for instance i deal coffee, at the midpoint between Queen and Dundas on Ossington, between Little Portugal and the Hipsters.

i deal's second location (the first is in Toronto's legendary Kensington Market), has all the shabby couches and stepping-into-someone's-basement-apartment-kitchen feel of the original on Nassau. As usual, the coffee's great, and the crowd lively. This is something that would have been unthinkable five years ago, when the cool part of Queen street petered out before Trinity-Bellwoods park, and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (Ossington ends at its main entrance) still remained a kind of psychological barrier for people in the community, keeping house prices low and shop fronts boarded up. That a great coffee shop and roaster like i deal would open up on Ossington leads one to believe it won't be long before the Vietnamese karaoke bars are replaced with places like this one:

It's called the Sparrow. Those heavy maroon blinds are always drawn, and when you can peer inthrough the door, you notice something rather unusual for much of Ossington - it's always busy. Always. I've never actually set foot in there, because I cannot imagine I have the icy coolness to survive in a place like this. And the menu speaks for itself:

This is ahistorical, decontextualized dining at it's best. Not a Vietnamese or Portuguese dish in sight – you could be anywhere in the city with this menu. It's a slice of trendy Queen Street for the people who can't stand Queen Street anymore and felt the need to colonize somewhere new.

And you see, this is the future of Ossington. The people in the Art and Design district who cannot stand people like me, moderately well-off bourgeois dilettantes with a keen eye who simultaneously manage to drain everything authentic out of a community and replace it with Subways and Starbucks (because it's what we know), need somewhere to go too.

Like those ethnic communities along Ossington, these people are fleeing something, in this case the gentrification and homogenization of Queen Street, where every little mom and pop store has a brand manager, and making their way to Ossington for something authentic. And I'm not too worried they'll take over Ossington, and its cigar factory (can anyone say an outdoor staging of Carmen?),

or its wine grape warehouse,

and turn them into a Banana Republic and a Quizno's. I want to keep thinking Ossington will defy the very descriptions I am trying to impose upon it.

My little excavation reveals a number of layers, each of which has influenced the later ones. The remaining Victorian homes from the turn of the century, alongside industrial buildings. One then finds the artifacts of the people who lived and live around here, through the ethnic communities. Finally, like much of Toronto when it undergoes gentrification, a kind of well-designed, poorly lit group of shops and restaurants, each trying to help lighten your wallet.

To me though, the most interesting spot on Ossington is this vacant block:

Why? Because despite all the business that has emerged in the past few years, it remains stubbornly empty. What should be the centre of Ossington's street life sits vacant. Right now this block is a bit of real space that contains a multitude of possibilities. It's been vacant for years now, but what can you imagine it to be? A bookstore? A architect's office? A Burger King?

I have neither the money nor the aptitude to reclaim this property from its empty misery. Someone will come along, and all I can hope is that whoever does reopen those doors appreciates the depth of history and multiple aspects to its character, and adds a new layer to an already complex urban space.

Moreover, instead of stealing from Beaudelaire and Benjamin, I'd prefer steal a concept from Foucault – well, I'm not even really stealing it from him either, I'm really just name dropping - and take you on a kind of archaeological dig through the history of Ossington as I imagine it to be. Our tools will be unequal parts empirical and conjectural, and best of all, there will be photos.

When you come at Ossington, heading south from Dundas Street, you find yourself in the centre of the Rua Açores, one of the Portuguese areas of the city.

[An aside. Toronto self-identifies itself as a massive agglomeration of “villages”, represented by street signs letting you know what “village” you're in. Could it be that nice-looking street signs are a major reason why Toronto is, for the most part, a decent place to live? I wonder how all the people who live in these areas deal with the kind of village they're a part of. And if you think they don't, consider this – I'm rooting for Portugal in the World Cup this year.]

Here you have some of the elements of what makes an area “ethnic” - the local butcher and fishmonger sell dead things with their heads on them. The peixaria pictured above is a particularly interesting and affordable place to buy fish from. You won't find sushi-grade tuna there, but there are a kinds of fish there that I've never seen anywhere else in the city.

The papelaria in the photo is also a sign of another ethnic influence on Ossington – Vietnamese. Yes, the Papelaria Portugal is run by a Vietnamese family. And so here we find the two communities who make up what I'll call the “ethnic presence” on Ossington – Vietnamese and Portuguese. (yes, that is a strip club above the pool hall).

The Portuguese presence appears to manifest itself through food and building materials. The Portuguese community is well known in Toronto for helping to supply manual and skilled labour in the building trades for the booming construction industry here, although a good number of Portuguese were recently deported back to Portugal by the Conservative government.

So there are hardware stores, kitchen and bath stores, bakeries and fishmongers – one could do nearly all their renovating shopping on a single block of Ossington.

The Vietnamese presence is very different. Where the Portuguese community lacks restaurants, the Vietnamese community abounds. I believe there are six Vietnamese restaurants on Ossington Avenue between Queen Street and Dundas Street. Many of these restaurants also have Karaoke, as you can see from the picture below.

Ossington wasn't always this way. If the information on this site is correct, Ossington's name, like many streets in Toronto, is an homage to a distant British nobleman. In this case, the 1st Viscount Ossington, John Evelyn Denison, whose family owned the area immediately west of Ossington.

Ossington is also home to those seeking refuge from the crowds and rents of Queen Street West. Also known as West Queen West, the area along Queen to the east and west of the foot of Ossington is arguably the hippest place in the city, with shops, art galleries and restaurants galore. One can see how West Queen West is beginning to bleed over onto Ossington, just as the Portuguese influence made its way south along Ossington from Dundas. In between these two influences is a kind of everyman's land, where old and new mix with the hip and ancient.

Take for instance i deal coffee, at the midpoint between Queen and Dundas on Ossington, between Little Portugal and the Hipsters.

i deal's second location (the first is in Toronto's legendary Kensington Market), has all the shabby couches and stepping-into-someone's-basement-apartment-kitchen feel of the original on Nassau. As usual, the coffee's great, and the crowd lively. This is something that would have been unthinkable five years ago, when the cool part of Queen street petered out before Trinity-Bellwoods park, and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (Ossington ends at its main entrance) still remained a kind of psychological barrier for people in the community, keeping house prices low and shop fronts boarded up. That a great coffee shop and roaster like i deal would open up on Ossington leads one to believe it won't be long before the Vietnamese karaoke bars are replaced with places like this one:

It's called the Sparrow. Those heavy maroon blinds are always drawn, and when you can peer inthrough the door, you notice something rather unusual for much of Ossington - it's always busy. Always. I've never actually set foot in there, because I cannot imagine I have the icy coolness to survive in a place like this. And the menu speaks for itself:

This is ahistorical, decontextualized dining at it's best. Not a Vietnamese or Portuguese dish in sight – you could be anywhere in the city with this menu. It's a slice of trendy Queen Street for the people who can't stand Queen Street anymore and felt the need to colonize somewhere new.

And you see, this is the future of Ossington. The people in the Art and Design district who cannot stand people like me, moderately well-off bourgeois dilettantes with a keen eye who simultaneously manage to drain everything authentic out of a community and replace it with Subways and Starbucks (because it's what we know), need somewhere to go too.

Like those ethnic communities along Ossington, these people are fleeing something, in this case the gentrification and homogenization of Queen Street, where every little mom and pop store has a brand manager, and making their way to Ossington for something authentic. And I'm not too worried they'll take over Ossington, and its cigar factory (can anyone say an outdoor staging of Carmen?),

or its wine grape warehouse,

and turn them into a Banana Republic and a Quizno's. I want to keep thinking Ossington will defy the very descriptions I am trying to impose upon it.

My little excavation reveals a number of layers, each of which has influenced the later ones. The remaining Victorian homes from the turn of the century, alongside industrial buildings. One then finds the artifacts of the people who lived and live around here, through the ethnic communities. Finally, like much of Toronto when it undergoes gentrification, a kind of well-designed, poorly lit group of shops and restaurants, each trying to help lighten your wallet.

To me though, the most interesting spot on Ossington is this vacant block:

Why? Because despite all the business that has emerged in the past few years, it remains stubbornly empty. What should be the centre of Ossington's street life sits vacant. Right now this block is a bit of real space that contains a multitude of possibilities. It's been vacant for years now, but what can you imagine it to be? A bookstore? A architect's office? A Burger King?

I have neither the money nor the aptitude to reclaim this property from its empty misery. Someone will come along, and all I can hope is that whoever does reopen those doors appreciates the depth of history and multiple aspects to its character, and adds a new layer to an already complex urban space.

Wednesday, April 12, 2006

Wozzeck

The other Canadian Opera Comapny production this month was Alban Berg's Wozzeck. I have a special fondness for this work, and for the music of the Second Viennese School in general, so I was looking forward to seeing the full staging of this masterpiece yesterday. Alas, the current production was a disappointment.

The production itself was interesting, and the singing was pretty good, if a bit distant. I think where the production really let me down was in conductor Richard Bradshaw's handling of the score.

I don't know if was that he was conducting for the audience (there was no intermision in this short 3-act opera), but he seemed rushed, and there was little connection between what was going on in the pit and what was going on on stage. There were also some serious balance problems between singers and the orchestra, something I've never seen to this extent before at the COC.

At the end of it however, I think there was a fatal misunderstanding of the context in which Berg wrote the score. We tend to see the early atonal works as representing a break from the past. Although there is something to this from an analytic perspective, Wozzeck is very much a work imbued with a romantic sensibility. Where was the brief pause between the first and second beats of the waltz parts of Wozzeck? Where, if I may say it, was the warmth? It was all too cold, which may work with serialist Boulez works of the 1950's, but doesn't have a place in this piece.

Anyway, for a work that is rarely performed in Canada, this production could have been much more, especially given the COC's usual sensitivity and overall appreciation of other modern works for the stage.

The production itself was interesting, and the singing was pretty good, if a bit distant. I think where the production really let me down was in conductor Richard Bradshaw's handling of the score.

I don't know if was that he was conducting for the audience (there was no intermision in this short 3-act opera), but he seemed rushed, and there was little connection between what was going on in the pit and what was going on on stage. There were also some serious balance problems between singers and the orchestra, something I've never seen to this extent before at the COC.

At the end of it however, I think there was a fatal misunderstanding of the context in which Berg wrote the score. We tend to see the early atonal works as representing a break from the past. Although there is something to this from an analytic perspective, Wozzeck is very much a work imbued with a romantic sensibility. Where was the brief pause between the first and second beats of the waltz parts of Wozzeck? Where, if I may say it, was the warmth? It was all too cold, which may work with serialist Boulez works of the 1950's, but doesn't have a place in this piece.

Anyway, for a work that is rarely performed in Canada, this production could have been much more, especially given the COC's usual sensitivity and overall appreciation of other modern works for the stage.

Thursday, March 23, 2006

Bellini's Norma

Please indulge while I interrupt my dry attempts at political insight for something closer to my heart!

I'm too tired to attempt anything resembling a proper review, but if you live in Toronto, go see Norma. It's a great show, a tight two-act bel canto masterpiece that shows off Bellini's genius and points towards the paths taken later on by Verdi and Wagner, who both cite Bellini as an influence.

The production doesn't bog down, and the singing is great. It's worth the price of admission just to hear June Anderson skip up and down the scales in some of the coloratura passages with a delicacy and clarity one isn't used to hearing at the Canadian Opera Company.

Torontonians are a clap-happy lot when it comes to the opera, but she and the rest of the cast deserved it in this case. So Torontonians, go support your local big-box cultural institution and see Norma!

I'm too tired to attempt anything resembling a proper review, but if you live in Toronto, go see Norma. It's a great show, a tight two-act bel canto masterpiece that shows off Bellini's genius and points towards the paths taken later on by Verdi and Wagner, who both cite Bellini as an influence.

The production doesn't bog down, and the singing is great. It's worth the price of admission just to hear June Anderson skip up and down the scales in some of the coloratura passages with a delicacy and clarity one isn't used to hearing at the Canadian Opera Company.

Torontonians are a clap-happy lot when it comes to the opera, but she and the rest of the cast deserved it in this case. So Torontonians, go support your local big-box cultural institution and see Norma!

Sunday, March 05, 2006

Rodney Graham: Sincerity and Delight

This fall, the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal will host an exhibition of works by Vancouver-based artist Rodney Graham.

Two years ago, my daughter and I took our weekly Saturday morning trip to the Art Gallery of Ontario, also known here in Toronto as the AGO. Art galleries are at their best on a Saturday morning. It’s usually quiet, just you and whatever you happen to be looking at, and it’s a good time to take a child, as they can ask questions and linger at the works they enjoy, something I’ve discovered kids are more apt to do than adults.

On the façade (now just a memory) of the AGO was a giant poster of a man in a convict’s outfit playing a piano. It looked goofy, and given my own conception of modern art at the time, led to a bit of an eye roll and I thought to myself, “I suppose we can always go downstairs and look at the Group of Seven paintings” (my daughter loves them).

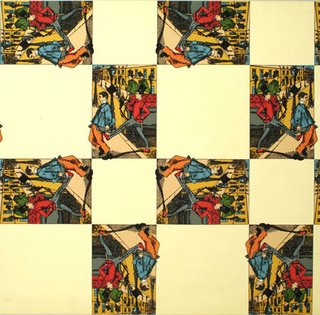

So we went upstairs to this new exhibition, and found nearly the entire second floor consumed by Rodney Graham's work. As you enter, the main walls were covered in the wallpaper at the top of this post (image from the Donald Young Gallery website). A man kicking another man in the ass. Things were looking up!

As we walked down the hallway, we could see that there were a number of small, dark rooms playing films.

Like many encounters with new works or events, it was the first work I saw that had the largest and most favourable impression on me. It was a short looped film entitled City Self/Country Self. It involved Rodney Graham playing both of the central characters, a bourgeois gentleman and an ambling country bumpkin.

When I walked in, the gentleman was getting his shoes shined, looking at his pocket watch. The bumpkin, walking down the street, looks up at a clock tower. The bumpkin starts to walk up a street, as the gentleman approaches him on the sidewalk. A carriage passes the bumpkin, who walks out into the street directly behind the carriage. The carriage drivers look over their shoulders, to watch the gentleman kick the bumpkin squarely in the behind. The kick is played slowly, over and over and over again, and then normal time resumes, the bumpkin picks up his hat, the carriage drives away, the gentleman walks up the other side of the road, and the bumpkin walks along and looks to a window where he fixes his hat, while the gentleman gets his shoes shined, and looking at his pocket watch. The bumpkin, walking down the street, looks up at a clock tower. The bumpkin starts to walk up a street, as the gentleman approaches him on the sidewalk…you get the picture.

I do not know how to describe this work any better than this. It is something you have to encounter to fully appreciate the richness, the initial humour and ultimately, the power of this film as a work of art. I sat there with my daughter for about 20 minutes, just watching it over and over again. There was no beginning and no end, just endless repetition. The moment you inserted yourself into the work was the moment the narrative started. You laugh the first time he gets kicked, but then the humour begins to fade, and you start to see it all as an elaborate trap, where both the viewer and the characters are locked in a struggle to come to terms with their place in the world.

Am I making too much of this? Perhaps, but his other works bore out a similar message.

It’s easy here to invoke Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal recurrence, keeping in mind Graham’s recurrence in his looped films is immediate, adding a kind of ruthlessness to the concept that I don’t know Nietzsche himself envisioned. The gentleman and the bumpkin know what’s going on, they are both players in this drama, and yet they never give you that winking eye, that twist to let you know that this is all bitter irony. I suspect this is because it’s not meant to be ironic.

This is what I believe both separates and lifts Graham’s work above many other contemporary artists. He is sincere. He wants you to laugh because you'll think about the arid, abstract things he wants you to think about more easily. However, he doesn’t wink, and let you know that you don’t have to take any of it seriously, even though his every work nudges you to laugh, to take it all lightly, to chortle in knowing amusement. Graham refuses to let go.

We are bathed in irony these days, and like God, despite rumours of its recent death, it corrodes our ability to judge or to know, and so it refreshes the spirit to see someone, as nonsensical as it may sound, do irony straight.

Nonetheless, his works are a delight to watch, to look at and be a part of. Graham hasn’t fallen for the trap that many contemporary artists do, that in depicting reality, we have to show the seedy or gritty side of things. Instead, works like City Self/Country Self finds its ultimately nihilistic message in a lovely medieval French town.

This is another thing about Graham’s work - it is beautiful. From his upside down trees, to his reading stand for a loop he discovered in Georg Buchner’s Lenz, Graham strives for his works to look beautiful. I wonder how this reconciles with his constant engagement with, broadly speaking, Romantic artists such as Wagner, Buchner and, dare I say it, Freud.

I wonder this because his works strike me as beautiful in a classical way, in the way a period staging of a Baroque opera is. The figures stop, they pose, and in that pose they represent our deepest feelings and thoughts. The realism in Graham’s work is formalized, idealized. (Only when talking about art can one talk about an idealized realism and mean it- logical positivists need not understand my words here, although they’ll get what I’m saying if they see Graham’s work.)

Rodney Graham’s art managed to recode my understanding and appreciation of modern art, and what it can be, how it can reconcile itself and negotiate with earlier periods and yet stay entirely modern in its mode of expression. These days, the Group of Seven or the impressionists no longer intrigue me the way they used to, and I’ve come to instead look forward to the latest works by living artists. I encourage anyone who is in Montreal this fall to visit one an exhibition of one of Canada’s greatest living artists. You may even want to pick up his latest rock CD, but that’s for another post.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)